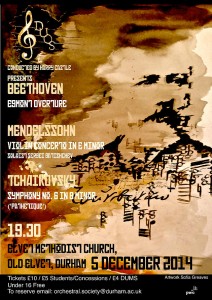

Durham University Symphony Orchestra spanned Romantic Europe last night in a concert at Elvet Methodist Church that pulsed with emotional intensity. All three works, Beethoven’s Egmont Overture, Mendelssohn’s violin concerto and Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony, the Pathètique gave conductor Harry Castle plenty of scope for drawing out a wonderfully rich texture, from the thrillingly dark chords that opened the Egmont Overture through to the double basses’ final dying sobs that end the Tchaikovsky.

Durham University Symphony Orchestra spanned Romantic Europe last night in a concert at Elvet Methodist Church that pulsed with emotional intensity. All three works, Beethoven’s Egmont Overture, Mendelssohn’s violin concerto and Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony, the Pathètique gave conductor Harry Castle plenty of scope for drawing out a wonderfully rich texture, from the thrillingly dark chords that opened the Egmont Overture through to the double basses’ final dying sobs that end the Tchaikovsky.

The layout of Elvet Methodist forced the big orchestra into a potentially unwieldy configuration: the strings were very spread out across the front with the basses a long way over to the right, past the gangway, and then the brass in a tight solid block a long back into the chancel, and Harry Castle did a great job of holding things together, achieving a good balance and most importantly, keeping the dynamic right for the building; and in terms of sound, the layout worked very well. The long wings of strings meant we were fully enfolded in the sound, and being behind the archway meant that the brass were able to give it all their force without being overpowering.

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture sums up the whole of Goethe’s play about the complex figure of Egmont, the Dutch hero who, helped to liberate the Netherlands from Spanish rule, but in doing so lost his life because he put too much trust in the nobility of his enemies. Harry Castle achieved an excellent balance between the darkness and light that characterises Beethoven’s piece, with richly heavy chords that oozed with heroic swagger and a sunny lilt in the lighter sections. The question and answer passages between the strings and the wind were particularly effective and there were some very nice wind solos here, and throughout the evening. Bassoonist Matt Burgess led a graceful gear change into the second movement of the Mendelssohn and his solo that opens the Tchaikovsky was rich and brooding, whilst Alice Burn brought sad dignity to the Pathètique clarinet solo.

In emotional terms, Mendelssohn’s violin concerto is the cheeriest of the three pieces on the programme, and the orchestra set out to make the contrast as strong as possible. Harry Castle took the first movement at a sprightly speed, with the lower strings giving a really solid pulse under the dancing. There was a surprising delicacy too amidst the fireworks that I didn’t necessarily expect from a student orchestra, although at the end of the first movement things briefly got a bit overheated and the ensemble was a little shaky.

Having a soloist who is also a regular member of the orchestra, often brings an extra dimension to a concerto performance, and this was definitely the case tonight with violinist Sergei Batishchev (who was back in the ranks after the interval for the Tchaikovsky). During the first movement in particular, there was a strong rapport between orchestra and soloist; after the cadenza, the orchestra really picked up on Sergei Batishchev’s arresting energy, carrying it on, as if they were giving a resounding affirmation that they had enjoyed they way he played. In the second movement too, they picked up the mood of his quietly smouldering song, creating an oasis of serenity. Harry Castle then gave the famous last movement a quirky springiness that made it sound fresh and playful and it was a lot of fun to listen to.

Fun doesn’t come into Tchaikovsky’s final work. The sixth symphony is relentlessly bleak, even in the waltz-like second movement, it’s just misery trying to disguise itself with a smile. It’s a piece where conductor and orchestra have to put aside any restraint, any English politeness, and just indulge shamelessly in the symphony’s agony.

There were many, many good details in this performance: the sinister weight of the carefully placed pizzicato in the strings that ended the first movement; the mournful ebbing away of the insistent timpani in the second; and the way the third movement march built up from a cautiously simmering start to a boldness in the insistently repeated little march theme that looked forward to Shostakovich’s bitingly sarcastic marches. Harry Castle brought the false ending of the third movement to a thrilling climax, but I sensed that he and the orchestra were too nervous of misplaced applause as they hurtled into the last movement with such a frantic rustle of page-turning that it took a little while to settle into the chillingly sombre mood of this movement.

The best part of this symphony though, in fact probably of the whole concert, was the searing expressivity of the first movement, the orchestra giving everything they could to achieve the intense passion that Harry Castle was asking from them. I was startled by just how much I was drawn right into to the world of despair that this symphony creates; the Russian orchestras do it best, of course, but if you can’t have Russians then perhaps students with all the intoxicating power of youth are the next best thing, and it certainly seemed that way tonight.