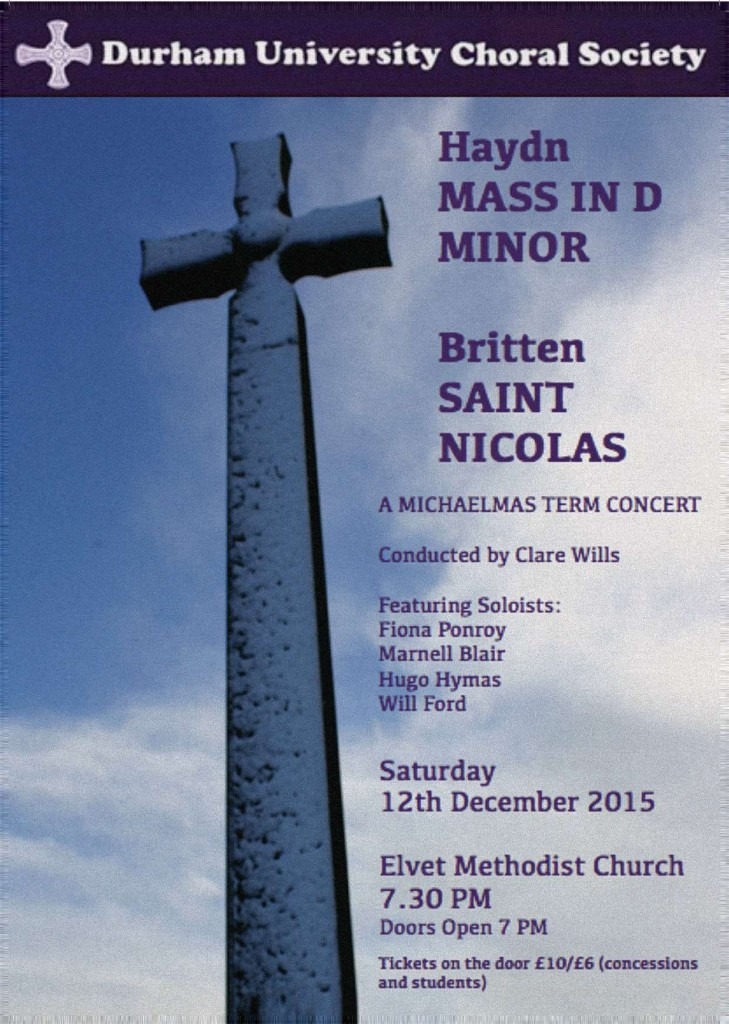

With the first Kyrie of Haydn’s Mass in D Minor, Durham University Choral Society made it clear that they were out to make an impact with their new conductor, Clare Lawrence-Wills. The opening chords rang out with a beautifully rounded sound that then developed through the movement, setting up an evening of excellent singing.

With the first Kyrie of Haydn’s Mass in D Minor, Durham University Choral Society made it clear that they were out to make an impact with their new conductor, Clare Lawrence-Wills. The opening chords rang out with a beautifully rounded sound that then developed through the movement, setting up an evening of excellent singing.

The piece is more commonly known as the Nelson Mass; a name it acquired after Nelson’s visit to Vienna, because the mass may have been performed as part of the music to honour his visit. It’s a cheerful, vibrant piece, with a pair of trumpets prominent throughout, lending it plenty of vibrancy – the trumpeters in tonight’s student orchestra were particularly good, blending in and out of the texture as required, and keeping up heroic levels of energy.

All the solo glory in the Nelson goes to the soprano, with the other three soloists taking much smaller parts. Soprano Fiona Ponroy launched the Gloria with a joyfully buoyant solo line which blossomed over the course of the piece, after a slightly shaky Kyrie. Bass Will Ford sang serenely in the “Qui Tollis” section of the Gloria, and the quartet of these two plus mezzo Marnie Blair and tenor Hugo Hymas were a well-matched blend for passages such as the Credo “Et Incarnatus”.

Under Clare Lawrence-Wills’s direction the choir combined solid confident singing, with a lightness and energy that kept Haydn’s music fizzing. The sopranos were particularly good in the Gloria, with high, clear singing, and after Haydn’s mysterious Sanctus over sonorous low strings, the whole choir danced triumphantly through the Hosanna. The Mass concluded with a confident, joyful “Dona Nobis Pacem”, the trumpets still going strong and the choir bouncing – think a less solemn version of Bach’s famous Dona Nobis Pacem.

Britten’s cantata St Nicolas goes beyond our jolly red-coated Santa Claus to the original legends associated with St Nicolas, the miracle-working bishop of Myra. It’s a thoroughly absorbing story, with a lively text by Britten’s regular librettist Eric Crozier, brought vividly to life by Britten’s music, and enhanced further by the intense characterisation that came from Clare Lawrence-Wills’s singers and from tenor Hugo Hymas in the solo role of Nicolas. I was completely gripped and absorbed by the scenes from Nicolas’s life, so much so that when the audience are invited to join in with the hymn All people that on earth do dwell, during Nicolas’s enthronement as Bishop of Myra, it seemed the most natural thing to do, because I felt so much that we were part of the story.

The energy that the choir put into the long narrative passages did full justice to Britten’s excellent word-setting. The tenors and basses, assisted by the surging waves of orchestral sound, were particularly effective in the story of St Nicolas’s ship caught in a storm, until they were calmed by Hugo Hymas’s soothing prayer. Later, when St Nicolas berates humanity at large for their sinfulness, Hugo Hymas was powerfully sorrowful, putting across uncomfortable truths far more effectively than many preachers.

Britten intended St Nicolas to be sung by amateur performers – it was written for a commission from Lancing College although, as in his later works in the same style, most notably Noye’s Fludde there is no sense at all that the musical writing has been dumbed down. What is very present though is a deep-rooted sense of a long tradition of popular English music, and Clare Lawrence-Wills really drew this out in the folky swing of the second movement, telling of Nicolas’s birth, and there was something about music for the penultimate movement “His piety and marvellous works” that has a very Christmassy feel to it. I also loved the icy cold depiction of famine and the infamous story of the pickled boys, with its achingly sad lament of the community for its lost boys and this made the slow build up of hope and rejoicing into a beautifully shaped Alleluia at the end even more effective.

The final section of St Nicolas brings the work together in a moving and satisfying conclusion. The orchestral colour when death summons Nicolas was both scary and dangerously alluring and Hugo Hymas, absolutely possessed with the character of Nicolas was passionately lyrical as he welcomed death against the choir’s subdued Nunc Dimittis. The cantata ends with the choir singing another great Anglican hymn, “God moves in a mysterious way” bringing this gentle reminder that there is more to Christmas than satsumas in stockings to an intensely moving close.