When Ailsa Dixon (1932-2017) studied music at Durham in the 1950s, women composers were absent from concert programmes and it was hard to name any who had made a career from their writing. It would be another half century before the musical world took seriously the need to redress the balance.Ten years ago Judith Weir was the first woman to be appointed Master of the Queen’s Music in four centuries since the post was created, and it seems the tide is turning at last. Alongside the effort to establish equal opportunities for today’s emerging talent, we are now seeing the rediscovery of composers from earlier generations whose work had been sidelined in musical history.

It’s now hard to imagine the barriers that were faced by female composers and the level of self-belief that was necessary to surmount them. In the nineteenth century, the composing careers of formidable musicians such as Fanny Hensel and Clara Schumann were severely restricted by the social climate in which they lived. Fanny’s father decreed that for a woman music ‘must be only an ornament, never the root of your being and doing’; her brother Felix Mendelssohn walked off with the credit for a number of her compositions, some of which are still being reattributed. Clara Schumann, a virtuoso pianist, was already composing concertos as a teenager, but later wrote, with a level of self-deprecation that now feels almost a betrayal of her gifts, ‘I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose — there has never yet been one able to do it.’ In the 1920s Elizabeth Maconchy was denied the Mendelssohn scholarship by the director of the Royal College of Music on the grounds that ‘you will only get married and never write another note.’ She is now recognised as one of the most important composers in 20th-century British music.

There was no formal tuition in composition in Durham in the 1950s and an absence of female role models in the music department. But Ailsa’s impulse to compose was strong, and during her time as a student she wrote her first substantial work, a Scherzo for string quartet. After graduating she went into teaching, and it would be many years before she returned to composition. In 1976 she produced Handel’s Theodora with a cast of her singing pupils; in the wake of this all-consuming project she looked for a new outlet for her creativity, and began to write an opera of her own. Letter to Philemon, based on an episode in the life of St Paul, was produced in 1984, and unleashed a decade of composing in which the majority of her works were written. A handful of performances at that time included songs and duets sung by Ian Partridge and Lynne Dawson and works for string quartet played by the Brindisi Quartet. But with no agent and little instinct for self-promotion, most of her music remained unheard until the very end of her life. In 2017, These things shall be, an anthem she had written 30 years earlier, was chosen for premiere as part of the Five15 project highlighting the work of women composers. Its first performance, in the spectacular glass-roofed concert hall surrounding the keel of the Cutty Sark in Greenwich, took place five weeks before she died.

This landmark concert began a revival of interest in Ailsa Dixon’s music, sadly too late for her to enjoy. The following years saw several posthumous premieres of works found in her archive after her death. A sonata for piano duet and three songs with string quartet were first performed at St George’s Bristol in 2018 and 2020, by which time the revival of her music was featured as the cover story in the British Music Society’s magazine. Her works have since been performed up and down the country, in venues from London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall to the Italian chapel in Orkney, digitised in Finland and France, and broadcast in America. A YouTube channel has been created for a growing collection of recordings, and plans are underway for a CD of her complete works for string quartet by the Villiers Quartet.

On 6th March, in the run-up to International Women’s Day, her music will be celebrated in a special concert in Durham, with singers and instrumental performers convened from the University’s Chamber Music Society and Keyboard Instrument Society. The range of works represented will make this the most extensive programme of her music performed to date, presented with an introductory talk.

The programme opens with These things shall be, the anthem whose first performance led to the revival of her work. A setting of words from a prophetic poem by John Addington Symonds, it looks forward to a future in which ‘new arts shall bloom of loftier mould, and mightier music thrill the skies; and every life shall be a song, when all the earth is paradise’.

Ailsa Dixon’s instrumental writing will be showcased in a range of works including movements from her sonata for piano duet Airs of the Seasons. When it was premiered in 2018, critic Frances Wilson wrote:

“The opening chords of the first movement are reminiscent of Debussy and Britten in their timbres, and the entire work has a distinctly impressionistic flavour. Ailsa’s admiration of Fauré for his ‘harmonic suppleness’ is also evident in her harmonic language, while the idioms of English folksong and hymns, and melodic motifs redolent of John Ireland and the English Romantics remind us that this is most definitely a work by a British composer with an original musical vision. The entire work, although quite short, is really delightful and inventive, rich in imagination, moods and expression.”

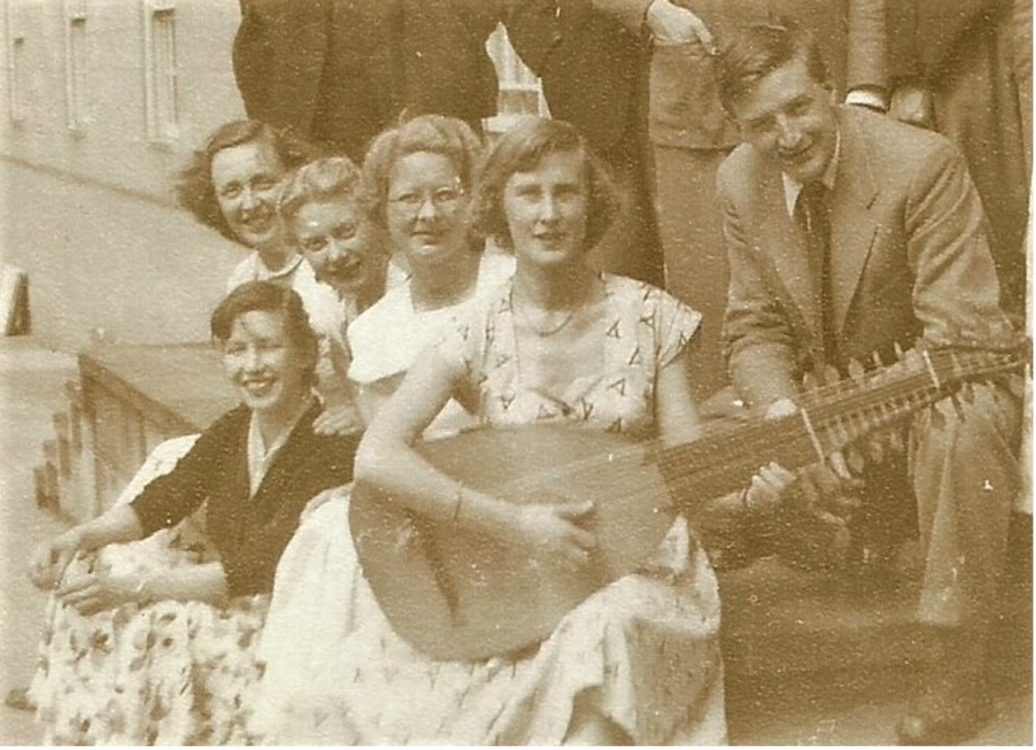

The programme will also feature songs, works for string quartet, and even a fugue for lutes. The lute was an instrument she particularly loved: she began playing while at Durham and a photograph of the time shows her holding her lute at the centre of a group of friends on the steps of St Mary’s College.

A founder member of the Lute Society in 1956, she is now recognised as one of the pioneer generation in the twentieth-century lute revival.

The concert in Kenworthy Hall at St Mary’s College will be followed by a drinks reception. Details here.

(c) Josie Dixon, February 2024