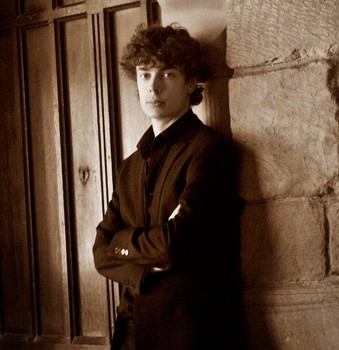

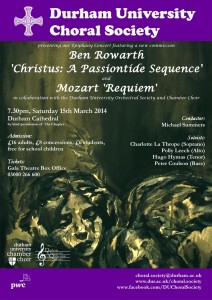

There are two works on the programme for Durham University Choral Society’s next concert. Mozart’s Requiem is one of the best-loved works of the choral repertoire, and needs no introduction, but what about the other piece, commissioned for this concert, Christus: A Passiontide Sequence. I spoke to its composer, Ben Rowarth, and to Mike Summers, Musical Director of DUCS to find out more about it. Ben Rowarth grew up in Hexham, graduated from Durham University last summer and is now studying for a Master’s in vocal ensemble performance with Robert Hollingworth at York. He has written a number of short choral works, mainly for his own ensemble, Renaissance. His motet “Where is thy God?” won the National Centre for Early Music’s young composer’s award in 2012 and received its first performance in Durham Cathedral at a concert given by the Tallis Scholars. Mike Summers explained that the commission for this concert came about because he was looking for a piece that could be performed jointly by the university’s choral society, chamber choir and orchestra. “Nothing in the existing repertoire for chorus, semi-chorus and orchestra was suitable, so it made sense to commission something to bring together the university’s three big ensembles, and after hearing the Durham Singers perform “Where is thy God?” last summer, I asked Ben to write something for us, and of course he’s a former Durham student too, which is a nice connection to have”. Christus: A Passiontide Sequence is Ben Rowarth’s longest, and most complex work to date. Knowing that the concert would be in Lent, and that the other work would be the Mozart, he compiled a collection of texts drawn mostly from the Tenebrae Responsories sung during Holy Week, and concluding with the words of the hymn It is a thing most wonderful. As the work was written to be performed in Durham Cathedral, the acoustics and structure of the building also played a part in the composition. The chamber choir, singing the Latin Tenebrae texts as a reflection on the English words sung by the main chorus, will move around the building, and the music allows time for the sound to travel through that great space.

There are two works on the programme for Durham University Choral Society’s next concert. Mozart’s Requiem is one of the best-loved works of the choral repertoire, and needs no introduction, but what about the other piece, commissioned for this concert, Christus: A Passiontide Sequence. I spoke to its composer, Ben Rowarth, and to Mike Summers, Musical Director of DUCS to find out more about it. Ben Rowarth grew up in Hexham, graduated from Durham University last summer and is now studying for a Master’s in vocal ensemble performance with Robert Hollingworth at York. He has written a number of short choral works, mainly for his own ensemble, Renaissance. His motet “Where is thy God?” won the National Centre for Early Music’s young composer’s award in 2012 and received its first performance in Durham Cathedral at a concert given by the Tallis Scholars. Mike Summers explained that the commission for this concert came about because he was looking for a piece that could be performed jointly by the university’s choral society, chamber choir and orchestra. “Nothing in the existing repertoire for chorus, semi-chorus and orchestra was suitable, so it made sense to commission something to bring together the university’s three big ensembles, and after hearing the Durham Singers perform “Where is thy God?” last summer, I asked Ben to write something for us, and of course he’s a former Durham student too, which is a nice connection to have”. Christus: A Passiontide Sequence is Ben Rowarth’s longest, and most complex work to date. Knowing that the concert would be in Lent, and that the other work would be the Mozart, he compiled a collection of texts drawn mostly from the Tenebrae Responsories sung during Holy Week, and concluding with the words of the hymn It is a thing most wonderful. As the work was written to be performed in Durham Cathedral, the acoustics and structure of the building also played a part in the composition. The chamber choir, singing the Latin Tenebrae texts as a reflection on the English words sung by the main chorus, will move around the building, and the music allows time for the sound to travel through that great space.

The work consists of three motets for the chorus and semi-chorus, three solo movements and three orchestral interludes scored for string orchestra and harp. “I had aspects of the Passion story in my mind that guided me when I wrote the orchestral interludes: the temptation of Christ, Pilate’s doubts during the trial, and finally the death of Jesus”, says Ben. He also explained that he wanted to set the Passion story in its wider context: “I wanted to put across the sense that the Jews have been waiting so long for their Messiah, so the piece opens with the choir singing plainchant settings from the Old Testament Lamentations, and texts for Advent. But now he’s here and being crucified, there’s doubt too – is this it? Is he really the Messiah or not?”. The narrative stops before Easter, and so the question is never really answered, but the words of the final motet “It is a thing most wonderful”, like the ecstatic closing choral of Bach’s St John Passion hint at the miracle of Easter. This final motet comes from one of Ben’s earlier piece – in fact he said he started there and worked backwards when composing Christus. I heard it performed by Renaissance in 2012; it retained the sense of the simple child-like hymn, but combined this with beautiful, yet surprising harmonies that carefully matched the drama of the words, and it will make for a lovely end to the larger work. Any composer writing music for Lent must feel the weight of history. Christ’s death and resurrection, the central message of the Christian faith, have, after all, inspired some of the greatest music in the western repertoire: works such as the majestic polyphonic settings of the Tenebrae texts by Renaissance composers and of course, Bach’s incomparable Passions. In Christus Ben manages to acknowledges his musical predecessors, without being encumbered by them. His imaginative compilation of texts and ideas gives a starting point for his own meditation on Christ’s final days, and musically he takes his inspiration from plainsong; a motif from the refrain of Allegri’s Miserere runs through the work, and he develops further musical ideas from the opening few notes of Bach’s St Matthew Passion. This awareness of the rich heritage of choral music is a theme that occurs throughout Ben’s music – “Where is thy God?” takes Taverner’s “In Nomine” as its starting point – and talking about influences, he said “It’s hard for composers today when you’re encouraged to be original, but you also want to engage with the audience and give them something in a context that they can relate to”.  I asked Mike Summers and members of DUCS about how they were finding the piece so far, although they haven’t heard it how it all fits together yet, and of course with a new work, there are no recordings to guide the singers. Mike told me that harmonically, it’s fairly straightforward, and very much in the tradition of modern choral music, but what’s interesting for a large choir is the texture, with its layers of plainsong, and they’re enjoying the challenge of developing their technique to bring out the long, slow plainsong passages with a clean, well blended and sustained sound. Helen Pugh, President of DUCS said “Christus is very different from the standard oratorio repertoire and is therefore proving to be an exciting challenge to learn but we are all looking forward to bringing the different societies together to hear what the work will sound like as a whole. This is a wonderful opportunity for such a large number of Durham’s musicians to come together in the Cathedral to display the wealth of musical talent Durham has to offer.” Full details of the concert can be found here

I asked Mike Summers and members of DUCS about how they were finding the piece so far, although they haven’t heard it how it all fits together yet, and of course with a new work, there are no recordings to guide the singers. Mike told me that harmonically, it’s fairly straightforward, and very much in the tradition of modern choral music, but what’s interesting for a large choir is the texture, with its layers of plainsong, and they’re enjoying the challenge of developing their technique to bring out the long, slow plainsong passages with a clean, well blended and sustained sound. Helen Pugh, President of DUCS said “Christus is very different from the standard oratorio repertoire and is therefore proving to be an exciting challenge to learn but we are all looking forward to bringing the different societies together to hear what the work will sound like as a whole. This is a wonderful opportunity for such a large number of Durham’s musicians to come together in the Cathedral to display the wealth of musical talent Durham has to offer.” Full details of the concert can be found here