There are many reasons, musical and personal, why I’m looking forward to this Saturday’s Durham Singers concert. We’re going back to the chapel at Ushaw college, and if you’ve not been there, it’s worth coming just to have a look at this gothic-revival treasure, because it’s not generally open to the public. We sang there for a private event last year, but this is the first time we’ve put on a concert there since we did the St John Passion in 2009. Not only does it look stunning, it’s also got a great acoustic, so it’s a real treat to sing there, particularly with the programme we’ve got lined up.

Although I generally enjoy most of what we sing, in the end, this is one of those programmes that had me excited right from the beginning. We planned it as a contemplative programme to mark the centenary of the First World War, but it goes beyond that, and as I worked on the publicity, I found all sorts of unexpected connections whilst discovering new things in the music too.

My personal task whilst learning the Byrd for this concert has been to stay focussed, and not allow myself to float away into a trance while I sing – something of which I was definitely guilty for a while. The solution, I realised, was to dig down into the music; to concentrate fiercely on everything going on around me; to know where all the interesting bits are in the other parts, and how the alto line interacts with the other four – fortunately some timely rearranging of our rehearsal layout helped with that too, and it’s made me much more disciplined about listening to the other parts in everything we sing. (Yes, I know, it’s about time too…).

As well as the Byrd, we’re singing two contemporary pieces, by Richard Rodney Bennett and Francis Pott. The Rodney Bennett piece, A Farewell to Arms is accompanied by a solo cello. The words come from two splendid Elizabethan poems, and reflect on the idea of turning swords into ploughshares, and of old soldiers laying down their weapons and casting off the passions of youth for dutiful, calm old age. There’s some lovely imagery in the texts, and the music really picks up on the sparkle of the words, although I wasn’t completely convinced by it until we had the chance to sing it with our cellist, Deborah Thorne, and then everything slotted into place.

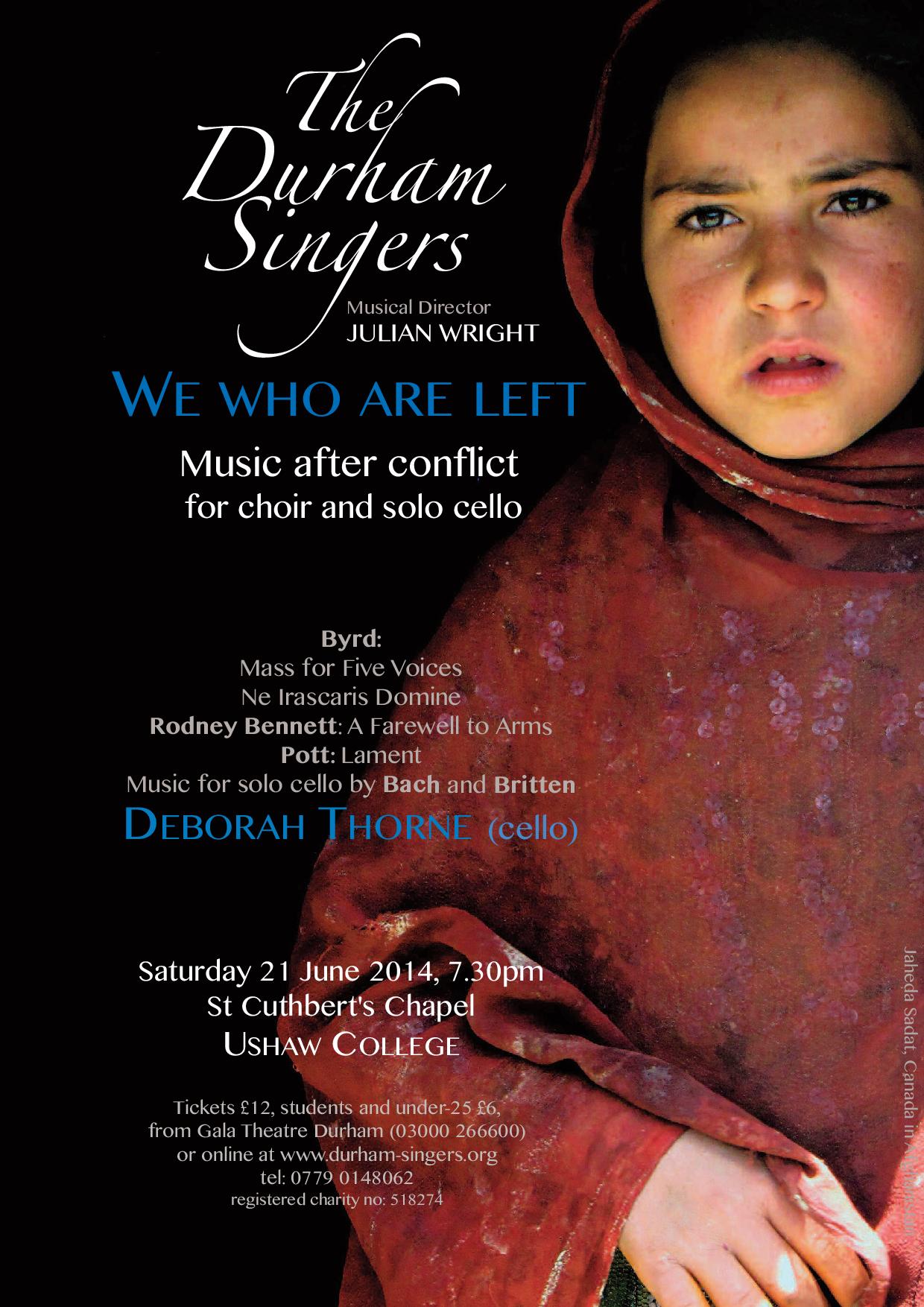

The opening lines of Francis Pott’s Lament gave us the title for the concert and it’s on this piece that the programme turns, for it makes the link between the specific idea of the First World War and the more general ideas about dealing with the aftermath of conflict that seep through the programme. It was composed in memory of a NATO soldier killed in Afghanistan and sets a poem written by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson in 1916. The poem is about how the all the common beauties around us are touched and sanctified by the memory of those who will never be able to enjoy them again, and the music is delicately poignant, with gentle but startling harmonies and lots of lovely movement hidden in the inner parts, which for me, give the music a sense of private grief.

Between our sung pieces, Deborah will be playing parts of the cello suites by Bach and Britten, and this, for me has been the source of my greatest musical discovery of the year. We listened to the last movement of Britten’s third cello suite at a choir practice to get a sense of the programme: I was immediately knocked senseless by it, and rushed off to listen to, and buy the whole lot. Britten wrote his suites for his friend Rostroprovich and slipped Russian folk tunes into the suites. There are several in the Passacaglia that ends the third suite, but then it ends with a sudden swerve into the music for the Orthodox church’s Kantakion for the Dead, very deep in the cello’s range; it skips the head and resonates right in my heart and guts. It was emotionally intense when I first heard it in January, and that’s now been amplified a thousand-fold because I’ve just been back to Moscow and have spent some very precious time with my adored Russian friends who I see very rarely, so the piece has now become very personal, and will forever be tied up with my own Anglo-Russian friendships.