After a gap of about twenty years, I’m stepping back into recorder performance in a concert that I’ve put together with my soprano friend Liz Roberts. It’s a short, informal evening in the cosy surroundings of St Chad’s College SCR (details here), and we won’t be printing a programme, so I thought I’d put a few notes on here about the recorder music, as it probably won’t be familiar to many people.

The theme running through the pieces is one of fantasy: sometimes, it’s playful, as in the Handel cantata, in Rubbra’s dreamy sonatina and in Britten’s cabaret songs but there are also more serious longings for something better – in Lasica ch’io pianga, and Love’s Philosophy, and there are elements of both in the mood changes of Handel’s sonata and Berkeley’s sonatina. The idea of the concert came when I heard a radio broadcast of Sophie Bevan and the Academy of Ancient Music performing Nel dolce dell’oblio at the Proms last summer – I immediately thought that Liz and I would have to have a go at it, and the rest of the programme developed from there. I wanted to showcase a few of the major works for recorder, from the baroque and from the great recorder revival of the twentieth century, and then the songs were chosen to match the recorder pieces.

Handel: Pensieri Notturni di Filli (Nel dolce dell’oblio) HWV134

Phyllis’ Night-time thoughts (In the sweetness of sleep).

In his early twenties, when he was still developing as a composer, Handel spent a few years in Italy studying the Italian style, and one of his patrons there was the Roman prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli. Opera had been banned in Rome because of a scandal, so instead the city’s aristocratic families put on private performances of cantatas and oratorios, opera-flavoured substitutes, in which there was no actual acting, but with all the dramatic musical content expected from opera. Nell dolce dell’oblio is one of the smaller of these works, and was written around 1707. Recorders were often used in baroque orchestras to colour idyllic pastoral scenes, or for softer moments, and the subject matter of this cantata covers both. Phyllis lies sleeping and Cupid fills her mind with images of her lover; she is convinced she is in his arms, but awakes to find it was all just a dream.

Handel: Recorder Sonata in A Minor HWV362

Largo-Allegro-Adagio-Allegro

By the 18th century, the recorder was being used less and less in orchestras: its narrow dynamic and tonal ranges meant that it simply couldn’t hold its own against more sophisticated instruments, unlike the flute, whose design was undergoing rapid improvements in the hands of Quantz and other flautists. The recorder remained a popular instrument for skilled amateur musicians though, and canny composers like Handel and Telemann realised that there was a commercial opportunity in publishing music for people to play at home. So lucrative was this market, that some of Handel’s sonatas were an early victim of publishing piracy, and a rogue, unauthorised edition has given editors headaches ever since.

Handel frequently borrowed and reworked his best material – his skill here lay in knowing what would work in different contexts. The recorder sonatas are full of tunes from his operas, and it’s possible that he Handel did this with the conscious intention of giving his fans the opportunity to play his greatest hits themselves. The A minor is my favourite of the six, and it’s the most dramatic of the set too, almost an entire opera in miniature. The opening Largo, with a bass line that uses an Agrippina aria Por ritorno a rimiravi, is noble and tragic. A tempestuous Allegro follows – it has a angry, stomping melody over a raging semi-quaver accompaniment. The Adagio is pleading, begging for something, and its opening motif recalls arias from Aci, Galatea e Polifemo and from Rinaldo. Finally, we have a jolly Allegro romp to bring things to a happy conclusion.

Edmund Rubbra: Sonatina op 128

Allegretto comodo-Adagio Mesto, Cadenza-Variations on En la Fuente del Rosel

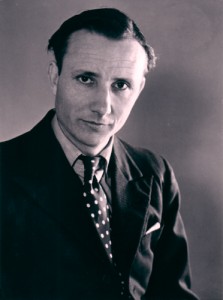

Edmund Rubbra was one of those quiet British composers who just got on with things, unaffected by the storms of twentieth century composition. He grew up in Northampton, then studied with Holst, with whom he shared an interest in Eastern music; he played piano for Diaghilev’s dancers, was friends with Finzi, was commissioned by the BBC to write something for the coronation, and was a lecturer at Oxford for many years. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Durham.

Edmund Rubbra was one of those quiet British composers who just got on with things, unaffected by the storms of twentieth century composition. He grew up in Northampton, then studied with Holst, with whom he shared an interest in Eastern music; he played piano for Diaghilev’s dancers, was friends with Finzi, was commissioned by the BBC to write something for the coronation, and was a lecturer at Oxford for many years. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Durham.

Like so much twentieth century English recorder music, Rubbra’s 1965 Sonatina Op 128 was written for Carl Dolmetsch, son of the early music pioneer Arnold Dolmetsch, and his long-time accompanist Joseph Saxby. The Dolmetsch family helped to bring the recorder out of obscurity, onto the concert platform with Carl Dolmetsch’s virtuosic playing, and into the classroom too, as they pioneered the design of plastic recorders and wrote tutorial books.

Rubbra’s sonatina is written for accompaniment on harpsichord or piano, which may explain its continuous motion underneath the dreamy lines of the recorder part. The first movement has a languid theme, around a faster, dance-like central section. The themes of the first and second movement are be slow, but Rubbra’s constantly shifting accents and unresolved modal harmony give them life and movement. The second movement ends with an improvisatory solo cadenza, in which the recorder is constantly trying to break free of something, only to be pulled down repeatedly, until at last, in quiet jubilation it escapes and soars up into the heights. The final movement is a set of variations on a 16th century Spanish song “En el fuente del Rosel”, in which a young girl and a squire frolic together in a fountain. Rubbra’s music here is by turns playful and sensuous, whilst also bringing together ideas from the first two movements into a unified and satisfying whole.

Lennox Berkeley: Sonatina

Moderato-Adagio-Allegro Moderato

Beginning in 1939, and then picking up after the war and continuing until 1989, Carl Dolmetsch gave an annual recital at the Wigmore Hall, and it was these recitals that produced the remarkable body of twentieth century English recorder music. Lennox Berkeley’s sonatina was written for the second 1939 recital and has remained a central work of the recorder repertoire.

Lennox Berkeley’s music is often unjustly overshadowed by that of his friend, Benjamin Britten. The two men were particularly close in the 1930s, sharing a house and collaborating on Mont Juic, a suite of Catalan dances. Although a closer emotional relationship seems to have been a possibility for a while, the two men took different paths – Britten met Pears and Berkeley eventually married (Britten was godfather to Berkeley’s son Michael, who is well-known today as a composer and broadcaster). Berkeley had taken a different path into composing from Britten, taking a degree in modern languages at Oxford, before studying with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, a move suggested by Ravel, who was a family friend. He converted to Catholicism and one of his most popular works is The Four Poems of St Teresa an intensely emotional work for mezzo-soprano and chamber orchestra.

The sonatina is technically quite demanding – there are some tricky fast passages and includes several top F#s that require the player to stop the end of the instrument with the leg (which is why I will be forced to perform in trousers and flat shoes!) but great fun to play and, I hope, to listen to. The first movement is seductively playful, but with some hints of nostalgia and loss too. The Adagio is incredibly serene, and gives the performer lots of scope to show how alternative fingerings can colour the recorder’s tone, then there’s a wickedly fun Scherzo to finish with.

The concert is in St Chad’s College SCR at 7.30pm on Friday 28 February – admission free. If you can’t make it, but you like the sound of the music, check out my Spotify playlist for the full concert: