Every so often, The Sixteen’s annual Choral Pilgrimage programme coincides nicely with our plans for Durham Singers, and when this happens, it gives me an excellent justification for making the journey up to Edinburgh for their choral workshop. Three years ago, they did a programme of Victoria motets a few months ahead of our Victoria Requiem concert, and this year the draw was John Sheppard, who is on the programme for our Durham Singers March concert. I’m a big fan of Sheppard anyway, although as far as I remember, I’ve never actually sung anything by him before. I love the excessive false relations which give the music that distinctive extra bite, and as he composed most of his music during the Catholic reign of Mary I, there are lots of settings of vivid Latin texts.

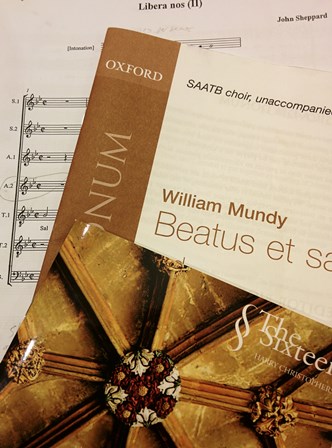

The choral workshops are open to anyone, but to make it worthwhile, you have to be capable of learning your music in advance and able to get straight into working on style and music – there’s no note-bashing. There are limited places in each voice part too, so sopranos and altos in particular need to book early, then you get sent the music about a month beforehand. The workshop is led by The Sixteen’s Associate Conductor Eamonn Dougan, with soprano and music editor Sally Dunkley on hand to offer lots of interesting scholarly background. I was particularly fascinated by her insights into how the printed editions of this music that we take for granted are the product of so much painstaking reconstruction. The reason John Sheppard’s music took longer to reach wide attention than that of Tallis or Byrd was because the tenor part book for much of his music was missing, so it’s all had to be reconstructed. Of course the nature of this sort of work is such that the talented editor has to disappear into the background – when they’ve done their job well, they’re all but invisible, and its easy to forget about them. Sally made us look at Francis Steele’s tenor part for Mundy’s Beatus et Sanctus and made us see how it just looks visually right when you look at the dots on the page and compare it to the other parts, even before you hear it.

One of the nice things about a four-hour long workshop, with no concert pressure, is that there was plenty of time over warm-ups, and Eamonn managed to cover some useful bits of technique at the same time. He had a good range of really physical warm-ups that served the double purpose of making me feel nicely relaxed whilst also helping me to visualise in new ways what the air and sound are supposed to be doing when I sing. It mostly reinforced what I’ve been told before, but one or two things about breathing suddenly became clearer.

Onto the music, and we began with William Mundy’s Beatus et Sanctus. Normally the workshops cover music from The Sixteen’s Choral Pilgrimage concert programme, but the length and voicing of the pieces by Mundy from the concert made them impractical for a workshop, so instead we had this shorter motet. Mundy was a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, and we probably know him best for his lovely English anthem O Lord the maker of all thing (it’s in Oxford Tudor Anthems). Beatus et Sanctus is in a similar vein – building up from simple imitative entries to cries of exultation, where we were all encouraged to sing out and let the sound sparkle through every part. Eamonn talked a lot about early consonants in this sort of music – getting the vowel to come on the beat. This was not new to me, thanks to previous workshops and the excellent music direction we get in Durham Singers, but it’s one of those things you can never be told too many times, and it’s always good to come at it again as if it’s something new.

Sheppard’s second Libera Nos setting I had heard at the Sixteen’s concert the previous night in Durham and it’s on our programme for March, so I was paying particular attention when we got onto this. Sally Dunkley pointed out that seven-part writing was unusual for this time (Sheppard’s dates are c.1515-1559) when plainsong still formed the bread and butter of most services, so this setting, with its theologically significant number of parts must have been quite special. The plainsong is always there though, with a short intonation before underpinning the music in the bass line. Singing plainsong is always tricky; it looks easy but you have to concentrate like mad to get the syllables in the right place, and after a couple of slips in the bass intonation, Eamonn threatened that anyone singing it wrong again would have to buy the entire section a round: there wasn’t a single mistake after that.

The key to singing renaissance music well is to get a really good legato line going. It’s easier on Sheppard’s long melismas, especially when they’re on a nice open vowel and on a passionate word, as in the opening “Salva”, but, we learnt, we have to keep doing it through every note, and every word. While we worked on this piece, Eamonn talked about the importance of getting really stretchy crotchets, again with early consonants to make the most of the vowel. He also had a lovely trick for the end of the piece. During the warm-ups he got us to visualise floating the sound high up into the air and he particularly asked us to do this on the final chord, at the end of the word Trinitas. The final a floated off, and then he closed his hand for the final s only after the sound had almost disappeared. It was very tidy and very effective.

Pacelli’s Veni Sponsa Christi was something completely different – Pacelli was a counter-reformation Italian composer who was recruited by the King of Poland to provide his court with good Roman Catholic church music. The music itself was written out in the original long notation, with breves and long notes going across bar lines and as it actually went at quite a lick, counting proved quite a challenge until I’d got it figured out. Once it started coming together it was great fun to sing, full of life and energy – the sort of music where it’s hard to keep still and you want to sing with your whole body. I think it was at some point while we were rehearsing this that Eamonn told someone off for visible toe-tapping but raised the point about where in our bodies we feel rhythm – something I’d never really thought about before. I tend to feel the beat somewhere in my stomach which now I think about it is probably contributing to some of the things that go wrong with my breathing and support, so that’s another thing to go away and work on.

So, gorgeous music, scholarly insights and a lot of useful technique – and the people at Greyfriars Kirk lay on a really good selection of cakes for the break.